Alumni Profile: Dr. Steven Lash (MS orthodontics, 1972) – Bringing precision and passion to orthodontics and to making American period furniture20 min read

__________________

Steven Lash is highly accomplished in two worlds where he thrives on very different types of challenges.

There is Dr. Steven Lash, the West Bloomfield dentist who specializes in orthodontics and is an adjunct clinical professor at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry. As he nears retirement, he has performed hundreds of orthodontic procedures, from basic teeth-straightening to much more complex procedures as an orthodontist working in tandem with surgeons to correct craniofacial anomalies.

Then there is Steven Lash, the woodworker. Over the course of his life, he has evolved from making simple wood toys as a child to a national-class, if not world-class, maker of furniture, most of it Early American. How good is he at making period furniture? One of his creations, a reproduction of the case that holds the glass armonica invented by Founding Father Benjamin Franklin, now resides at the Franklin Museum in Philadelphia.

In his dentistry world, patients, colleagues and the residents he has taught for decades know an orthodontist who is relentless, thorough and precise in the course of planning and completing dental treatments. Most have no idea of his woodworking life. There’s no room for furniture-making conversation when the subject at hand is how to proceed with a Bilateral Sagittal Split Ramus Osteotomy.

Similarly, in the narrow universe of highly skilled makers of American Period furniture, Lash’s fellow aficionados may know he is a dentist, but they focus on a much different result of that same relentless, thorough and precise nature that defines him. It’s about his decades-long research into and reproduction of beautiful, difficult-to-make pieces of furniture, the next one more impressive than the last.

Lash is a man of many stories about dentistry and woodworking and he doesn’t hesitate when asked how he first got interested in each. “I can tell you the exact date for both,” he says.

Dentistry and orthodontics

Lash traces the start of his journey into dentistry to one day when he was 11 years old and playing street hockey in his native Detroit. He was hit in the mouth with a puck, which fractured a front tooth. His mother, who didn’t drive, walked him the three-quarters of a mile to the family dentist. It was the beginning of a long series of treatments. “I spent time and time and time in the dental office,” he recalls. The dentist was his hero for fixing his teeth and eventually became a friend who introduced Lash to the sport of squash, which would come in handy later during his orthodontics residency at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Lash’s childhood dental experience didn’t immediately convince him to become a dentist, but he spent so much time in the dental chair that he felt comfortable with the profession. He decided to pursue it during his second year of undergraduate studies at Wayne State University in Detroit. He attended what was then the University of Detroit School of Dentistry, earning his DDS degree in 1968. He spent the next two years in the U.S. Air Force, stationed at McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey. He provided full-service dentistry for Air Force personnel and their families for a year, then volunteered to lead the base’s pediatric dental care for his second year. It was during that time of working with children that he realized he wanted to pursue orthodontics. He applied for a residency in that specialty at the U-M dental school and was accepted. He moved to Ann Arbor with his wife Carol and spent 1970-72 immersed in orthodontics clinical education and research.

“It was like manna from heaven,” he says of his time working with the leaders in orthodontics and oral surgery who were on the U-M faculty. They included renowned oral surgeon Dr. James Hayward, chair of the dental school’s Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, and Dr. Reed Dingman, an OMF and plastic surgeon who had started the U-M hospital’s plastic surgery department.

Lash was interested in malocclusions that went beyond the scope of conventional orthodontics, often requiring orthognathic (jaw) surgery by a team of orthodontists and surgeons. For his master’s thesis, Lash completed a retrospective comparison of surgical cases led by Hayward and Dingman. Beyond the educational benefits and career advancement gained through his association with the venerable Hayward, there was a personal perk. Lash remembers the cachet of being called out of a group meeting by Hayward’s assistant who announced, “Dr. Hayward wants to see you.” “It was my signal to get up, run outside and get into his Volkswagen Beetle and we’d go over to the Intramural Building and play a round of squash,” Lash reveals now, thankful that his family dentist had introduced him to the racquet sport years earlier.

After earning his master’s degree from U-M in 1972, Lash returned to the University of Detroit dental school to teach while working part-time for two orthodontists. After accepting an offer to buy one of the ortho practices, he gradually reduced his teaching commitment and transitioned from a part-time orthodontics practice to a full-time one, which he relocated to West Bloomfield.

Lash continued his interest in complex cases above and beyond the standard orthodontics practice. In the early 1970s, he began teaming with Dr. Jeffrey Topf, an OMF surgeon at Sinai Hospital in Detroit. They collaborated on a patient who needed a form of jaw surgery called a Bilateral Sagittal Split Ramus Osteotomy to advance the mandible. Lash believes it was a very early collaboration between an orthodontist and surgeon on this procedure in Michigan. The pair went on to collaborate on hundreds of orthognathic surgeries.

The team approach had not been the norm for orthognathic surgery in the past. Given Lash’s interest and growing use of the method, the U-D School of Dentistry in 1973 asked him to start and direct a new Orthognathic Surgery Clinic, which he did for 15 years. Another collaborator he worked with extensively was Dr. Ian Jackson, a ground-breaking surgeon from Scotland and the Mayo Clinic who relocated to Providence Hospital in Southfield and established a Craniofacial and Cleft Palate Clinic. Beginning in 1985, Lash became one of many members of Jackson’s team approach for complex surgeries.

For any number of reasons – often genetic, sometimes injury – patients with craniofacial anomalies may need facial, jaw, neural or skull surgeries, among others. “And when we sit in a room to discuss the case with various types of surgeons, dentists, orthodontists, speech or occupational therapists and other specialists, the bottom line is that the patient has to be able to chew when everything is done,” Lash said. “And who is responsible for getting that patient to chew? It’s the orthodontist and the prosthodontist and the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. That’s the importance of the dentist.”

Even while Lash was involved with orthognathic surgery at Sinai, Providence and Beaumont hospitals over the years, he was maintaining his practice in West Bloomfield. He was joined by his daughter Rebecca Rubin after she earned her DMD at Harvard and her master’s degree in orthodontics from U-M in 2002. Today, as the senior Lash approaches retirement, he is no longer taking new patients and serves as his daughter’s back-up.

What hasn’t changed is Lash’s commitment to teaching new generations of dental students and orthodontic residents about what he has absorbed in orthodontics and oral surgery over the last 55 years. After his time on the faculty at the University of Detroit, Lash became an adjunct faculty member at the U-M School of Dentistry in 1994. In 2013, he served for a year as Program Director for its Clinical Fellowship in Craniofacial and Special Care Orthodontics. Today, as an adjunct clinical professor of orthodontics, Lash continues to bring his wealth of knowledge to the U-M residents two days a month.

“Teaching – I just enjoy it,” he smiles and shrugs as though he can’t explain it further. “I enjoy when I can come up to a resident who is doing something and walk by them and I’ll just say, ‘Try it like this.’ And you’ll see the light bulb go on. My goal is that they’ll know far more than I ever know. And they will. I sit in conferences now and they are doing techniques that I didn’t have when I was practicing. They are doing things now that are just amazing.”

Woodworking and making furniture

The day Lash points to for the start of his interest in woodworking is the day, at age 9, when his tonsils were removed. Since the doctor ordered that he stay in bed for a week, Lash’s parents decided they would find something to occupy him during the recovery. They bought him a small scroll saw – a Dremel No. 1 – and he began trying it out that week in bed. He says the sawdust collection system was a bed sheet that his mother would occasionally gather up and take to his bedroom window to shake out.

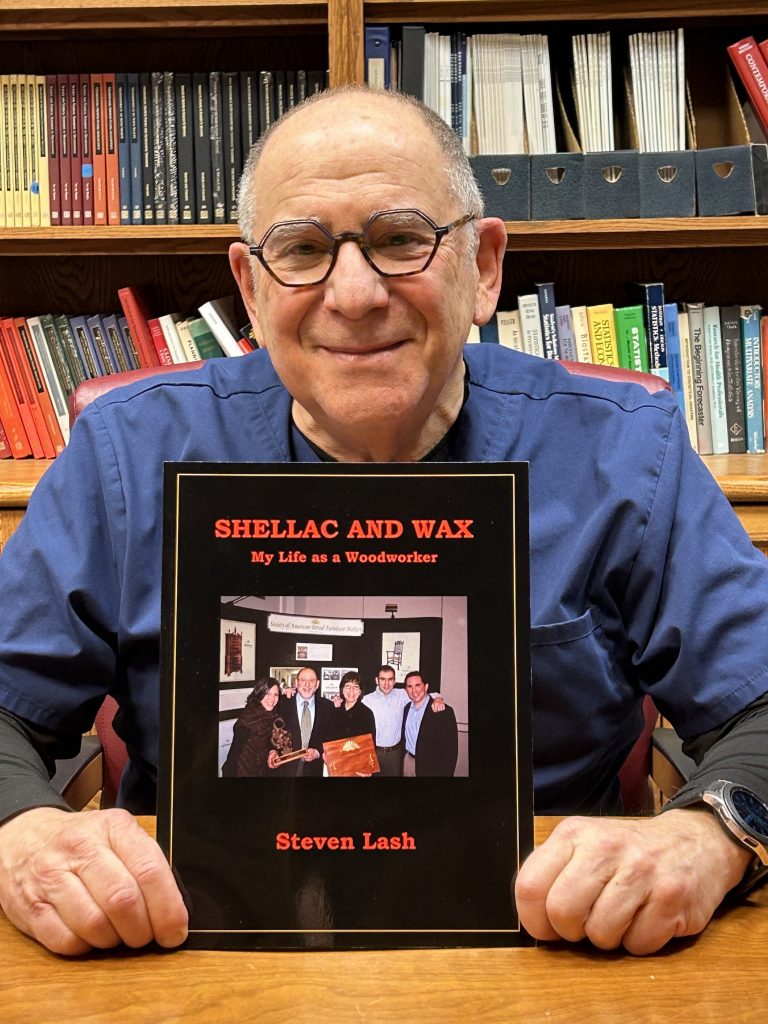

“That little gray electric saw opened a whole new world for me and, ever since, my passion has been to make things out of wood,” he writes in a 102-page, self-published book about his furniture-making entitled, “Shellac and Wax; My Life as a Woodworker.”

Soon Lash was turning out toys made out of wood – soldiers, guns, knives, swords, shields, an army helmet and other “implements of destruction” that he and his brother Myles saw in movies at the Mercury Theater. Teachers in elementary and middle school industrial arts classes helped young Steve build more sophisticated projects, including model yachts that he entered in the Detroit Public Schools regatta at Belle Isle. Those projects were helped along by two woodworking tools he had received as gifts at his bar mitzvah when he turned 13 – a Stanley No. 4 bench plane from friends of his parents, and a Dormeyer electric drill set with a circular saw attachment from his parents. It seems highly unlikely, he muses, that any kid today would be given a bench plane or electric drill as a 13th birthday present.

Lash is grateful his parents and teachers fed his interest in what they probably thought would be nothing more than a nice hobby. It has turned out to be a significantly richer story than that, a fascinating lifelong journey that has taken Lash around the country and to Europe to conduct research, deliver lectures and inspect notable period furniture, including pieces at Windsor Castle and historic Ham House near London, England. Somehow, Lash has managed to fit his furniture avocation in and around his career as an orthodontist.

In his book, Lash explains the oftentimes serendipitous ways he would become interested in a certain piece of historical furniture. Once a piece captured his imagination, he would begin a vigorous research process using authoritative woodworking and furniture books, journals, magazine articles, museum visits and his fast-growing network of woodworking friends around the country to obtain the precise measurements and construction intricacies. Along the way he needed to learn countless new and difficult woodworking techniques, just the sort of intellectual challenge he thrives on. Lash’s family – wife Carol and their children, Joe, Rebecca and Matt, and now their grandchildren – are an integral part of the process, often helping in his shop and traveling to the various exhibitions of his work. National woodworking magazines have featured his furniture, and he has lectured and written numerous articles explaining how he completed various projects, several of which have won awards.

A few highlights:

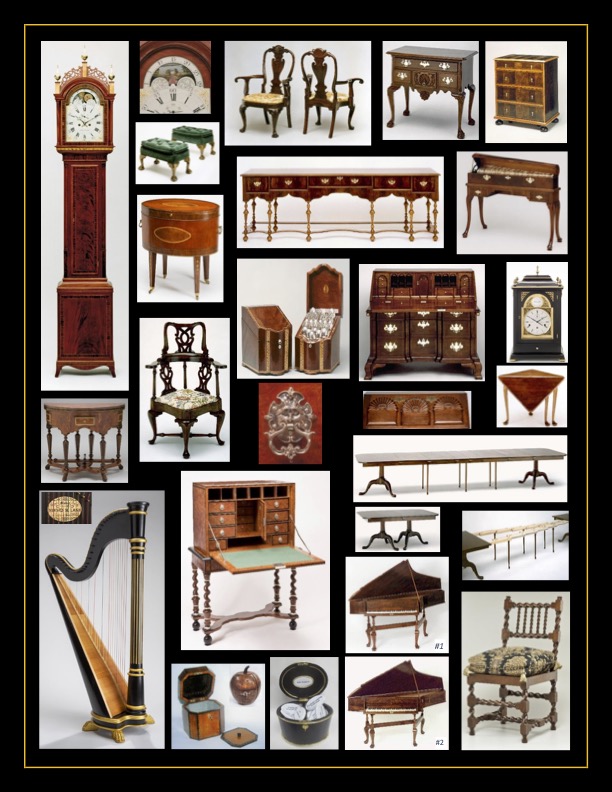

• Lash was in dental school in Detroit when he and Carol decided they wanted a grandfather clock. They couldn’t afford to buy one, so Lash made one. It was the first large project in what would become a furniture portfolio of increasing complexity.

• He next made several smaller clocks with names connected to their history and features – bracket, school, single- and double-steeple, pillar and scroll, and banjo clocks.

• A visit to the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Delaware, near the end of Lash’s Air Force commitment in 1970,was instrumental in focusing his interest on early American furniture.

• During his time in Ann Arbor for his orthodontic residency at U-M, from 1970-72, Lash made several trips to the Detroit Institute of Art so that he could examine early American furniture on display there and take notes with the idea of reproducing one of the pieces. Enthralled with a beautiful Philadelphia Queen Anne Highboy, he decided he would reproduce only its lowboy base, which would still be a considerable challenge. He would need to measure its dimensions, take photos and look inside its drawers and outer framework to understand how it was made. He asked for permission in advance and was refused. During a later in-person visit, he took as many notes as he could without violating the rules, but in the end decided he had to measure the piece and take photos. He would be careful; what would it harm? A museum guard caught him in the act, his film was intentionally exposed to ruin it and he was kicked out of the institute. He saved his notes and had enough information to later create the lowboy with its carved legs, ball and claw feet, and intricate carvings of vines and shells. The ironic epilogue of the story is that three decades later, after he had become a master builder of American period furniture, Lash joined the Associates of the American Wing of the art institute. He served on that board for 12 years and was its president from 2013-15. He and Carol, who collects art by American female artists, remain active in supporting the art institute that once kicked out the young wannabe furniture maker.

Other projects:

• A desk by early American furniture-maker John Goddard, with highly detailed carvings and 29 drawers, including 10 that are secret.

• Two spinet harpsichords based on one made in Boston in 1769. Lash originally intended on making only one but halfway through the project he discovered he had received a significant incorrect measurement from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which held the original in its collection. Rather than destroy the work he had started, he compensated for the mistake by finishing the spinet as a slightly smaller version than the original. But that wasn’t going to satisfy his quest for perfection. So as he worked on the smaller version, he also in tandem completed a second harpsichord that was exactly true to the original. The two spinets were a four-year project, completed in 1985.

• Other reproductions based on historic examples: A William and Mary Sideboard; a Handkerchief Table; a five-foot-long dining table that expands to more than 14 feet; an English card table, circa 1710-1730; and a 19th century English harp.

In 1999, at a “Woodworking in the 18th Century” conference at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, Lash and a woodworking colleague discussed the need for an organization to support the many people interested in the historical production and current reproduction of American furniture. It’s a generous community that depends on shared knowledge of a highly specialized craft. The two friends decided to fill a void in that network by co-founding the Society of American Period Furniture Makers. Lash was president for the first nine years. Today it has a membership of about 2,000 amateur and professional woodworkers, educators, collectors, curators and conservators. There are about 20 chapters around the country and two internationally. The society produces a lavishly illustrated annual journal, American Period Furniture, and a quarterly online magazine, Pins and Tales, for its members. In 2010, the Society presented Lash with its Cartouche Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Among Lash’s many furniture-making adventures, he gives the most attention in his book to the story of how one of his creations ended up in the permanent collection of the Benjamin Franklin Museum in Philadelphia. Among Franklin’s many inventions was a musical instrument created in 1761 that he called an armonica. It is a series of glass bowls, centered next to each other along an iron rod, that each produce a different tone when “played” by rubbing wet fingers on them as they are rotated via a foot pedal. Franklin’s invention was a sophisticated version that allowed for more complex and beautiful music than the performances he had attended with musicians rubbing the rims of wine glasses. Mozart and Beethoven composed for his armonica.

Lash first saw an armonica in 1983 at a convention featuring early music. He became friends with a glassblower named Gerhard Finkenbeiner who had created a copy of Franklin’s invention without the wood case that houses Franklin’s version at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. Lash was fascinated and began his no-holds-barred research routine, traveling to the Institute to see the original armonica, protected behind glass with no access for the public. Conservators agreed to provide measurements to Lash and he plugged them into one of the computer-assisted design programs he has used to plan his projects. He spent two years making the case and stand to house a set of glass bowls created by Finkenbeiner. The instrument was completed in 1996 and over the next 20 years was played by world-class armonica musicians at several music events around the country, including at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In 2015, the Chief Curator of the Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia asked Lash if he would temporarily loan his armonica to the Benjamin Franklin Museum. The museum had just finished a popular, two-year exhibit that included Franklin’s original armonica, which the museum had borrowed from the nearby Franklin Institute. Lash agreed and he and his wife were amazed when they later visited the museum and saw the crowds who constantly gathered around the instrument. Curators eventually asked Lash if he would like to donate his armonica permanently “to the American people.” His reply: “How could I refuse an offer like that?”

Challenges faced and met

When Steven Lash, the orthodontist, talks about his official career, the common theme is using his education, training and experience to help patients dealing with a range of problems from important – such as a teenager’s need for corrective braces – to more complex craniofacial surgical cases. His professional life is also about teaching – sharing his knowledge and acquired expertise with dental students and orthodontic residents, which he has been doing for almost as long as he has practiced, which is to say five decades.

“I love dentistry,” he says, then adds, perhaps explaining that challenges are what drive him: “Dentistry is hard, hard work.”

The rewards are great, no matter the patient. “If you’ve ever seen a kid the day he gets his braces off and smiles with all those brackets off of his teeth …,” he trails off, picturing the scene. “And then his mother comes in and I’ll have a little consult with her. And she’ll say to her child, ‘let me look,’ and she sighs in happiness and her mouth falls open. There is no better feeling than that.”

It’s the same with more difficult cases. “The reason I’ve always treated kids with some kind of facial deformity, or some type of clinical craniofacial patient, or cleft palate patient, is that it is the same satisfaction. It is gratifying when you see this patient after you’ve put in so much time and effort; maybe you’ve treated them for 10 or 12 years. And then they look in that mirror and they say, ‘I really look good.’ It is very satisfying.”

When Steven Lash, the woodworker, is asked to explain his interest in making fine period furniture, his explanation is about a lifelong love of “making things with my hands.” His drive to make perfectly beautiful furniture is the same drive he takes with him to the dental office or dental school. “It’s that same excellence you strive toward for kids with severe facial deformities. These are children and adults who have problems that are beyond the scope of conventional orthodontic treatment. And that attracted me because I could make something – a plan or the actual devices – that would solve or significantly help their physical limitations. You are making something for them.”

Whether Steven Lash is making a healthier life for a patient or making a reproduction of a Founding Father’s one-of-a-kind armonica case, the challenge and result has always been the same – to make a beautiful thing.

###

More information on the Society of American Period Furniture is available on its website here. Using its search function, type “Lash” to see examples of some of Steven Lash’s furniture creations.

___________________

The University of Michigan School of Dentistry is one of the nation’s leading dental schools engaged in oral healthcare education, research, patient care and community service. General dental care clinics and specialty clinics providing advanced treatment enable the school to offer dental services and programs to patients throughout Michigan. Classroom and clinic instruction prepare future dentists, dental specialists and dental hygienists for practice in private offices, hospitals, academia and public agencies. Research seeks to discover and apply new knowledge that can help patients worldwide. For more information about the School of Dentistry, visit us on the Web at: www.dent.umich.edu. Contact: Lynn Monson, associate director of communications, at [email protected], or (734) 615-1971.