Dental School, Engineering collaborate to track spread of aerosols in clinics6 min read

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Romesh Nalliah, associate dean for patient services at the School of Dentistry, faced many daunting questions. Among them: How many patients could the school safely treat in its multi-chair dental clinics and how could it best protect patients and providers from coronavirus during appointments?

“It was March and April,” Nalliah said. “Nothing much was known about the virus. To be safe, we were seeing only four patients at a time in a 36-patient clinic. I just said, ‘We need help.’”

Most of the dental school’s various clinics are large rooms where faculty and students would normally be treating from 10 to 40 patients at the same time, each in an operatory, or cubicle, surrounded by 5-foot-high panels. That space configuration poses different challenges for the safety of patients and dentists than private dental offices, where a dentist is typically seeing one or two patients at a time in separate rooms. Various types of dental instruments, such as high-speed handpieces used for drilling or cleaning teeth, generate aerosol droplets, which can contain coronavirus. Research was lacking on how those droplets could travel in large clinics like those found at the dental school.

Nalliah reached out to the U-M College of Engineering. He had worked before with U-M’s Center for Health Care Engineering and Patient Safety and its director, Amy Cohn. She put him in touch with Margaret Wooldridge and André Boehman, professors of mechanical engineering, who agreed to set up a study using cameras, special lighting and other equipment to track how aerosols are spread.

Wooldridge, Boehman and their team of graduate students and post-doctoral fellows determined that they needed to focus on the dentists’ high-speed drilling. Drills spray water, which serves as a coolant during use. “We wanted to know specifically, where do the aerosols go?” Wooldridge said. “And what might we do to reduce the transport and fate of those aerosols?”

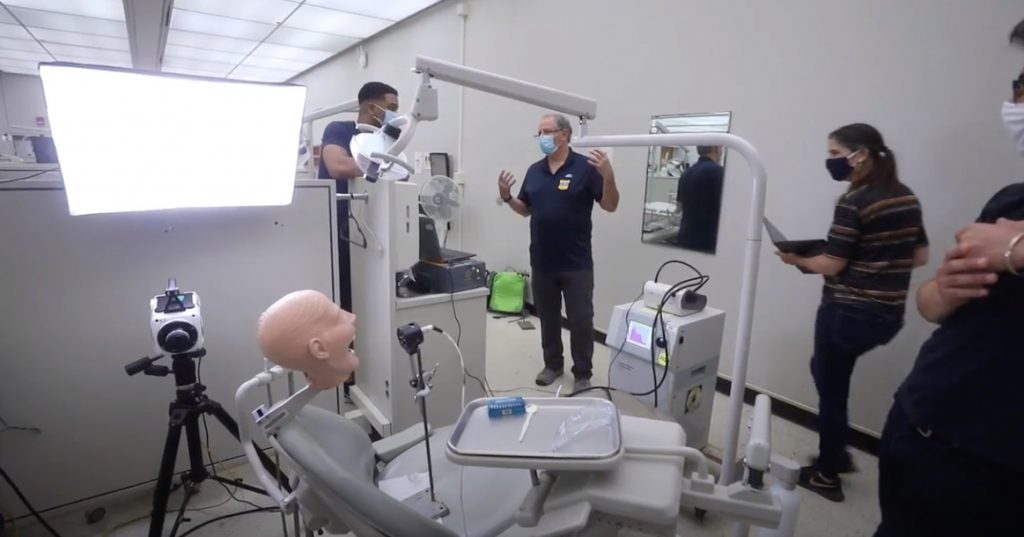

They used high-speed imaging, low-speed imaging and aerosol sampling to determine the pattern and distance of how aerosol droplets spread. A video camera recorded as Dr. Viyan Kadhium, a dentist and Nalliah’s research assistant, wielded the drill and practiced on a typodont, which is a mannequin head with plastic teeth that simulates patients.

Wooldridge said there are so many variables in dentistry that it was impossible to determine exactly where and how far the aerosols would spread in every situation. However, she and her team gathered enough data to determine that aerosols can travel from one cubicle into an adjacent one, potentially putting a nearby patient, dental students and faculty at risk. They also determined that plexiglass barriers added to the top of the standard cubicle walls can stop the particles.

“I was surprised at how variable the aerosols are that are generated by the dentist,” Wooldridge said. “I expected them to be more systematic and well-behaved, but they’re very erratic. They’re like a toddler at Meijer. In the candy aisle maybe.” Among the factors that can affect dispersion of aerosols are which tooth and tooth surface the dentist is working on, whether the dentist is left- or right-handed, the dentist’s posture and their hand position.

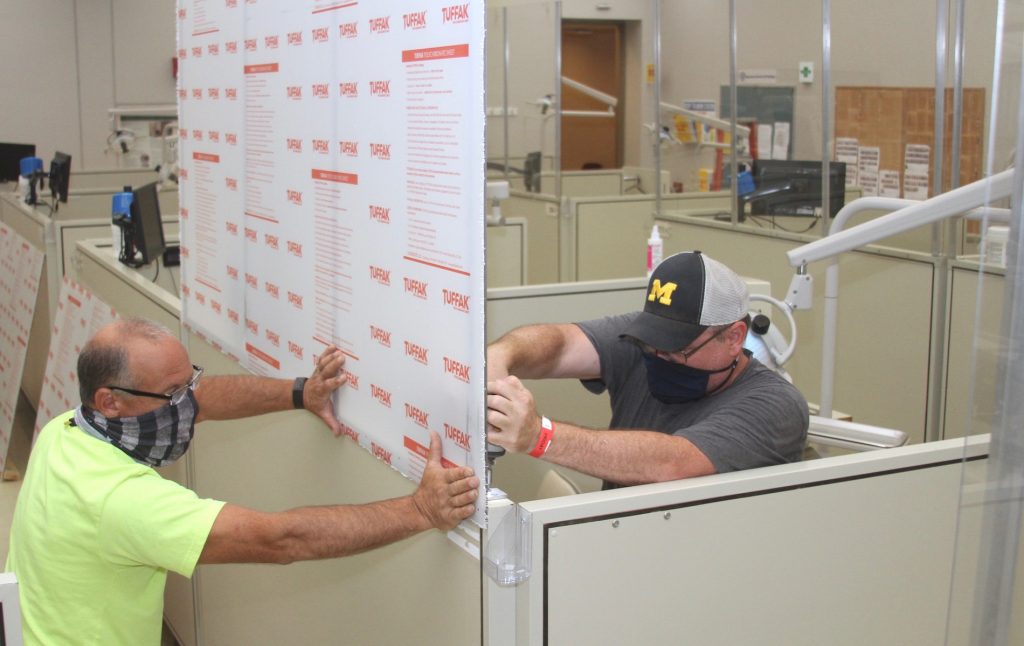

Once he had the engineering findings, Nalliah and Mike Folk, the dental school’s building manager, consulted with Michigan Medicine airflow experts, then researched the dental school ventilation system to determine the direction that air flows through clinics. Based on the aerosol and airflow data, plexiglass barriers were added to the top of some of the cubicle walls. It was not as simple as putting plexiglass around every cubicle because that could inhibit airflow. “Inhibited airflow means there would be a risk of stagnating, which increases the risk of transmission to subsequent patients,” Nalliah said. That means some cubicles are still going unused, but clinics with plexiglass can now safely support about 50 percent of their capacity, an increase from the more limited number when the pandemic first arrived.

The barriers were initially installed in four clinics, which increases the number of patients that can be seen around the school at one time. Some clinics may add the additional barriers later as the current plexiglass shortage eases.

Nalliah said the ability to call on the expertise of researchers at the College of Engineering was invaluable. “The capacity that we have now is still limited, but much better than what we were first facing.” Given the evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, more such collaboration may be necessary. “It’s an ongoing, ever-changing, dynamic situation,” Nalliah said. “And the whole world’s response to it as well as the dental profession’s response to it is ever-changing. We might need Margaret and André’s help again.”

See related story and video on the College of Engineering website here.

###

The University of Michigan School of Dentistry is one of the nation’s leading dental schools engaged in oral health care education, research, patient care and community service. General dental care clinics and specialty clinics providing advanced treatment enable the school to offer dental services and programs to patients throughout Michigan. Classroom and clinic instruction prepare future dentists, dental specialists and dental hygienists for practice in private offices, hospitals, academia and public agencies. Research seeks to discover and apply new knowledge that can help patients worldwide. For more information about the School of Dentistry, visit us on the Web at: www.dent.umich.edu. Contact: Lynn Monson, associate director of communications, at [email protected], or (734) 615-1971.