Student Profile Q&A: Shawn Hallett is nearing the end of his 7-year DDS/PhD dual degree program, but his journey of scientific understanding is just getting started12 min read

____________________________

This profile is one in an ongoing series highlighting School of Dentistry alumni and students.

____________________________

Shawn Hallett’s quest to become a dentist-scientist has produced a lengthy CV with incredible breadth and depth in complex scientific research and extensive collaboration with leading researchers around the country. Over the last seven years at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry, Hallett has completed the challenging dual-degree program that in May will yield both a DDS degree and a PhD from the school’s Oral Health Sciences and U-M’s Rackham School of Graduate Studies. Along the way, Hallett has been first author on six papers and co-author on nine others. He’s received nearly 45 awards, grants and fellowships from national healthcare and research organizations and institutes. He has traveled widely to deliver dozens of poster and oral presentations at conferences and educational institutions. Among his leadership positions, he is the immediate past president of the National Student Research Group of the American Association for Dental, Oral and Craniofacial Research. Dental school faculty member Dr. Renny Franceschi, who chaired Hallett’s dissertation committee, describes Hallett’s success this way: “Shawn displays all the characteristics one would hope for in a successful scientist – intelligence, curiosity, creativity and perseverance. I feel confident in saying that Shawn Hallett is one of the most outstanding young scientists I have had the pleasure of working with over the past 40 years.” In a recent interview, Hallett discussed his background and path that led him to pursue both a dental degree and PhD.

Q: Why dentistry?

A: I knew when I was growing up that I wanted to be dentist. Something about it gave me a deep fascination. My childhood dentist, Robert Leland, was a great role model – the way he approached patient care; his dynamic career treating all kinds of patients; leading a team; knowing the business side of it. You need to wear many, many hats and be a really efficient delegator of tasks, which I really appreciated. When I decided I wanted to be a dentist, he was a super advocate for me, very supportive, and I still keep in touch with him today.

Q: You majored in biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of Massachusetts and graduated cum laude from the Honors College there in 2016. Is that when you began to add scientific research to you career interests?

A: Like many students who decide on a dual DDS-PhD, we go in knowing we want to be a dentist first, then through some way or another we get the research bug. That happened for me when I was an undergraduate. I started doing research when I was a freshman, into breast cancer and tumor progression, looking at the efficacy of different cell cycle checkpoint inhibitors on breast cancer cell’s ability to metastasize. I thought this was super cool. It had nothing to do with dentistry, but it was the realization that, wow, we can design an experiment, think about all the various aspects of it, look at how to revert these cells to become not tumorigenic, basically. After graduation I spent two years as a Research Technician in the Center for Regenerative Medicine at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. My research there, using zebrafish as a model, was in the design and modification of single-guide RNAs using the CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate mutations in target genes that regulate proper craniofacial development. It had applications for cleft palate and rare craniofacial genetic mutations. Through working in a number of dynamic research environments, I began to draw the intersection between understanding more about biology and disease and then still having an appreciation for clinical care and hands-on patient interaction.

Q: How did you link up with the U-M dental school?

A: I made a connection in 2015, the summer after I came back from an undergraduate study-abroad program. I coordinated with faculty member Dr. Yuji Mishina to work in his lab for nine weeks because it is craniofacial research, closer to dentistry than some of the other research I had been doing. I was able to engage with some of the clinicians and the dentist-scientists who have gone through this program here at U-M. That validated that I wanted to do craniofacial developmental biology research, and also that I wanted to see patients as a dentist. I applied, was accepted and started here in 2018. I started in the lab of faculty member Noriaki Ono. When he left for another faculty position, I transferred into the lab of Renny Franceschi. I’ve continued to work with Dr. Mishina, and the fourth member of my dissertation committee, Dr. Benjamin Allen, a U-M Medical School faculty member in Cell and Developmental Biology who works with our OHS program.

Q: Earning either a DDS or a PhD alone is challenging; doing both over seven years requires an incredible amount of focus and dedication. How have you approached it?

A: I was adopted from an orphanage in Romania when I was a baby. When I was growing up, I always had a deep curiosity about where I was from, my roots and everything. So I’ve always had this innate curiosity that stems from my upbringing. It sort of propelled me into what I do now, where I ask deeper questions about science and biology to understand why things are happening and why things are how they are. The other part of my upbringing that had a big influence is growing up in a working-class family – super hard-working – in a rural, working-class area in southeast Massachusetts, about 30 miles south of Boston. My adoptive parents are amazing. They didn’t graduate from college, never had anything handed to them. That was definitely instilled in me as I’ve gone through my education and training. I think that has made me into a very persistent person. In my leadership positions and mentoring, I try to foster that development in the next generation of scientists or dentist-scientists or just people in general, trying to bring the best out of them, trying to be resourceful. So my curiosity and determination and work ethic are things that I always had growing up.

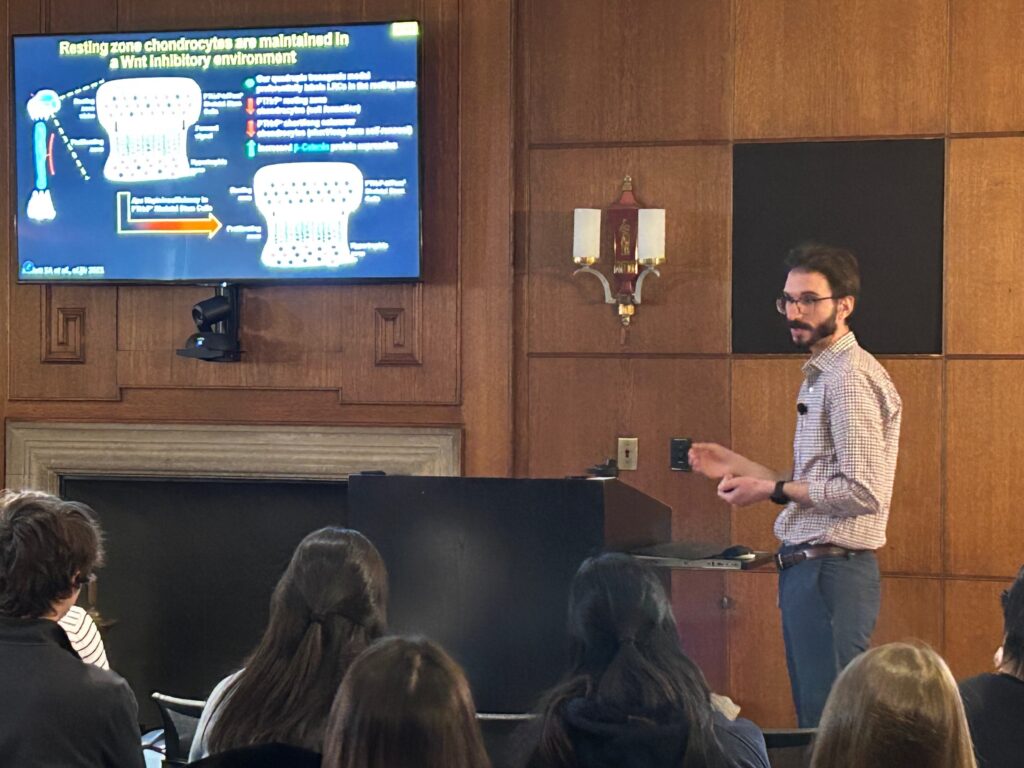

Q: During your time here, you have focused on a variety of research paths, with an emphasis on bone growth, including the function of skeletal stem cells and their regulation in the growth plates of bones. You recently successfully defended your dissertation, “Elucidating the Molecular Regulation of PTHrP+ and Fgfr3+ Chondrocytes in Diverse Endochondral Tissues.” How would you summarize your main research for the non-scientist layman?

A: The skeleton protects our body’s soft tissues and provides structure and support for bipedal locomotion. Importantly, there are over 700 skeletal diseases characterized by mutations in more than 500 genes, many of which require invasive surgical treatment or a lifelong commitment to medications to treat. My work has focused on determining the genetic regulation of skeletal development. When genes go awry throughout these processes, the manifestation of skeletal diseases persists. Ultimately, my work aims to identify novel pharmacologically-targetable genetic pathways that, when targeted in contexts of disease, result in proper development, growth and maintenance of the skeleton, thus improving quality of life and longevity of people.

Q: Your seven-year schedule for the dual degree started with about three years of getting your research momentum under way, then the didactical and clinical dentistry training dominated over the last four years, though you have continued to mix in research throughout the entire seven years. Tell us about your time so far in treating dental patients.

A: Patient care is obviously so important. The patient sits down in the chair and says, ‘My face hurts’ and there is swelling and other problems. What do you need to do right there and then to get that patient out of pain? It’s one of the only careers where you can do a procedure and then see the result of your procedure very quickly. Patient in pain; patient not in pain, maybe 30 minutes or an hour later. Also developing a rapport and trust with a patient, and a long-term relationship, is important. You can discover chronic medical conditions or systemic illness that they aren’t even aware of when you see them in the dental chair. It’s a really reaffirming career in that sense.

Q: Your patient care of late has brought you back full-circle to your initial fascination with how scientific discoveries can lead to therapies and breakthroughs that will benefit patients.

A: The medical expression is “taking bench to bedside” but in dentistry it is “bench to chairside.” What’s the reason behind a disease or condition or craniofacial anomaly? Why do patients present with more teeth than they should when they are growing up? Or maybe they have Sjogren’s Syndrome or other genetic diseases that have oral manifestations through their teeth or salivary glands. Or oral cancer. What’s the etiology? I want to investigate that, probe that a little bit deeper. I think the best way to do that was to model those diseases in the lab, understand the biology, the molecular regulation of these different pathways and these different proteins. Taking what you can do in the lab and bringing it to the patient. The ultimate goal is to provide less invasive, more innovative treatment options for patients, rather than, for example, surgery, which is so invasive and difficult for the patient.

Q: After you graduate in May, what’s next?

A: It’s kind of funny now that I’ve finished my dissertation, everyone is like “oh, you’re done now, right?” Like I’m going to throw out my lab notebook. No! I still have three papers to do and lots of other projects. But my next career move is that, starting this summer, I’ve accepted a postdoctoral fellowship focusing on genome editing of human hematopoietic stem cells with Dr. Daniel Bauer at the Boston Children’s Hospital. I wanted to do something different in my post-doc that was clinically translational but got me a little bit uncomfortable where I could learn some new science. I’ll do that and I also want to practice general dentistry one day or a half-day a week as an associate in a private practice in the Boston area. My wife, Megan, is a neonatal ICU nurse just finishing her pediatric primary nurse practitioner training, so she’ll be looking for a position in the Boston area as well.

Q: Boston will be handy if you want to run any more Boston Marathons.

A: I’ve run eight marathons, five of which were in Boston, in 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022 and 2023. My personal best is 2:52. I was injured last year but I did a half-marathon recently, so I’m getting back into shape.

Q: But will you have time to train as you adjust to your new post-doc research regimen?

A: That’s the thing about scientific research. There are always more questions to ask. It’s just a matter of being reasonable with how you can have the bandwidth to do everything. I think that is the challenge. You take on so much as a scientist, which is fun, but it can also be overwhelming at times. I think my wife helps keep me in check. It’s all just a huge balancing act in life.

###

The University of Michigan School of Dentistry is one of the nation’s leading dental schools engaged in oral healthcare education, research, patient care and community service. General dental care clinics and specialty clinics providing advanced treatment enable the school to offer dental services and programs to patients throughout Michigan. Classroom and clinic instruction prepare future dentists, dental specialists and dental hygienists for practice in private offices, hospitals, academia and public agencies. Research seeks to discover and apply new knowledge that can help patients worldwide. For more information about the School of Dentistry, visit us on the Web at: www.dent.umich.edu. Email: [email protected], or (734) 615-1971.