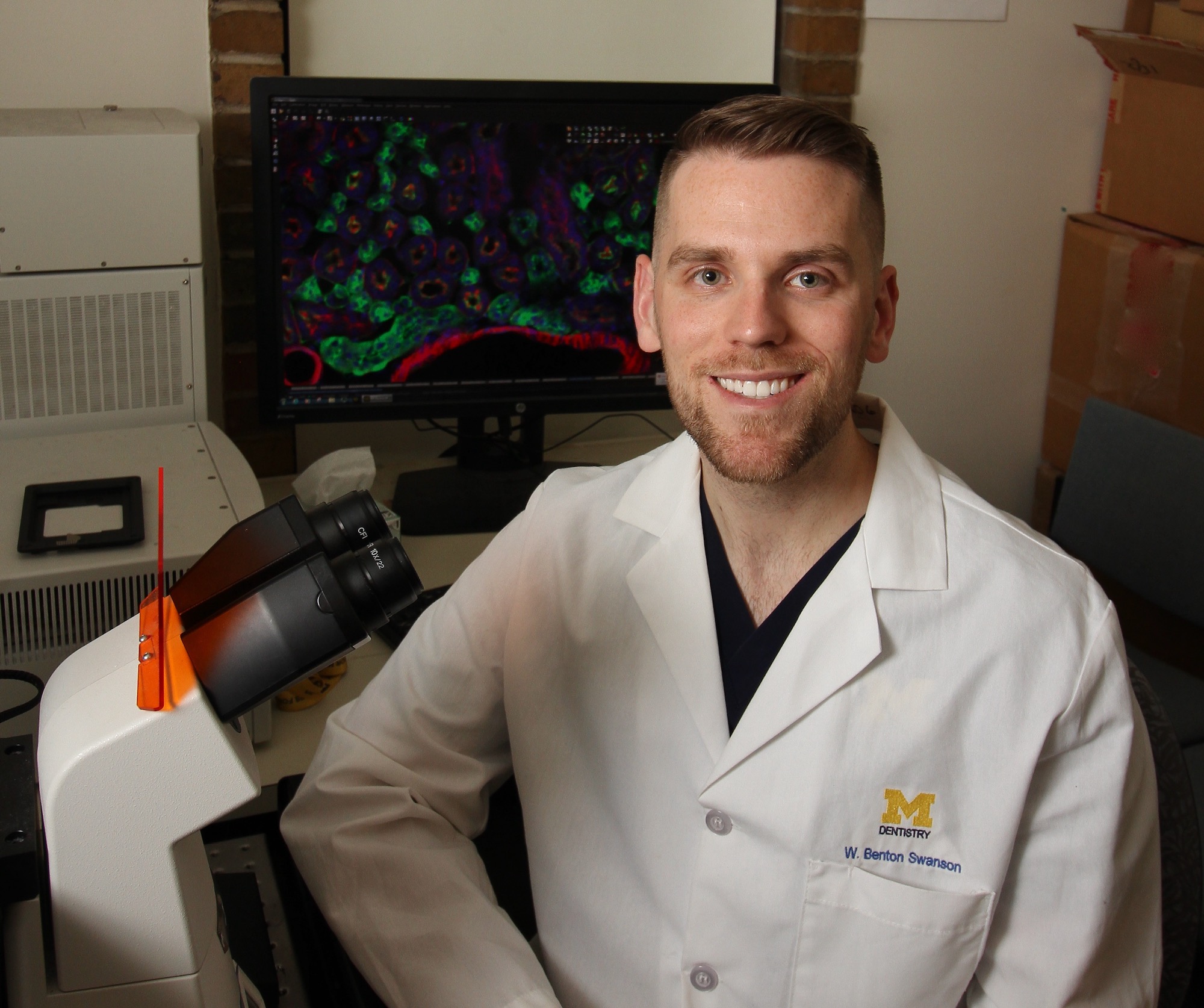

Student Profile: With a dual DDS and PhD, Ben Swanson brings a ‘clinician-engineer’ vision of scientific discovery and new technologies to clinical care15 min read

Ben Swanson’s seven-year sojourn in Ann Arbor has been an educational tour de force packed with clinical dentistry training, advanced scientific research, and business and entrepreneurial studies.

When he leaves the University of Michigan School of Dentistry after commencement in May, he’ll hold a Doctor of Dental Surgery degree and a PhD in the Oral Health Sciences. He’ll also take with him experience from his time at U-M’s Ross School of Business that furthered his interest in how entrepreneurs create companies to translate scientific discoveries into clinical care that benefits patients.

Swanson’s quest for a dual DDS-PhD is shared by about half of the approximately 20 students in the dental school’s PhD research program at any given time. Merging the four-year DDS program with the PhD program, which typically takes five years, requires focus and commitment, which Swanson embraced from the first day he walked into the school in the summer of 2017. Dual-degree students work with their faculty mentors to determine an individualized schedule of how to allocate their time over seven or eight years in order to complete their research dissertation while also meeting the didactic and clinical care requirements of the DDS.

While all seven of Swanson’s years at the school have been a blend of DDS training and PhD research, he leaned more into the research side of his training early on because he knew the process leading to a dissertation would take an immense amount of groundwork and learning. He needed to narrow his research interests to a singular track with the help of faculty mentors, then step into a lab and begin the regimented scientific research process that is full of twists, turns and course corrections. Once his research path was making good progress, it was easier to schedule the DDS requirements over the last two or three years.

Swanson had come to the U-M campus with an aggressive mindset for finding resources and mentors who could help him complete his chosen course of study – resources not only at the dental school but across campus and in the broader reaches of academia. The COVID-19 pandemic that hit in 2020 altered the usual routine of dental school and life in general, but educators, researchers and students, including Swanson, found ways to keep moving forward.

“When I first came here, I had come from a small town, a small high school, a small undergrad college, where everyone who I needed was always an arm’s length away,” Swanson said. “So when I came here, it would have been really easy to be intimidated by being one of 50,000 students. I’d never had that feeling before. But on the other hand, I was so used to reaching out and making connections and getting to know people. Here the medical school, business school, engineering college were all close, so there were a lot of resources, both programs and people. I looked at who and what resources I could leverage to help me during the seven years I was going to be here.”

Why dentistry and research?

The small hometown he references is Bemus Point, New York, in far western New York, about 65 miles southwest of Buffalo and 20 miles east of Lake Erie. Swanson liked science and math as a child, with chemistry kits as a favorite pastime. That led to his major of chemistry, paired with finance, when he attended Canisius University in Buffalo. He spent his undergrad years exploring a variety of educational interests and how they might become a career. He had kept dentistry on his list after being impressed with the skills of his childhood orthodontist and her involvement in his hometown community life. To learn more about dentistry while at Canisius, Swanson made connections and spent time observing at the nearby University of Buffalo School of Dentistry. He liked what he saw, but there was another significant development at Canisius that also influenced his career choice.

For the first time in his academic journey, he was exposed to scientific research and the faculty members with PhDs who conducted it. Swanson was struck by their passion and dedication to studying a narrow slice of science for many years until they were leaders in their specialized area, even as they acknowledged there was so much more they would continue discovering in coming years. “They were so excited about it and wanted to continue doing it,” Swanson said. “They were faculty, but in a sense they were still students. And I thought that was really cool.”

Swanson then began to explore how he might combine his newfound interest in research with dentistry. “I got the research bug and was curious: How do you become more involved in healthcare? How do you become more involved in what’s the latest and greatest in that area? You can be a follower, but how do you be a leader? I learned that there are people who balance both dentistry and research, so I began exploring PhD options to go with dental training.”

That search convinced him that pursing a career that merges PhD and DDS degrees would be personally meaningful and keep him intellectually challenged and engaged long-term, not just in the short run like some other professions might. “Michigan was the place to come to get all that exposure under one roof,” he says. “Things that were important to me were phenomenal engineering and translational research, an engine for getting things out into the world. A university focused on translation and interdisciplinary research, and certainly the clinical education. To find that all under one roof was a no-brainer for me to come to U-M once I was accepted.”

The course of discovery

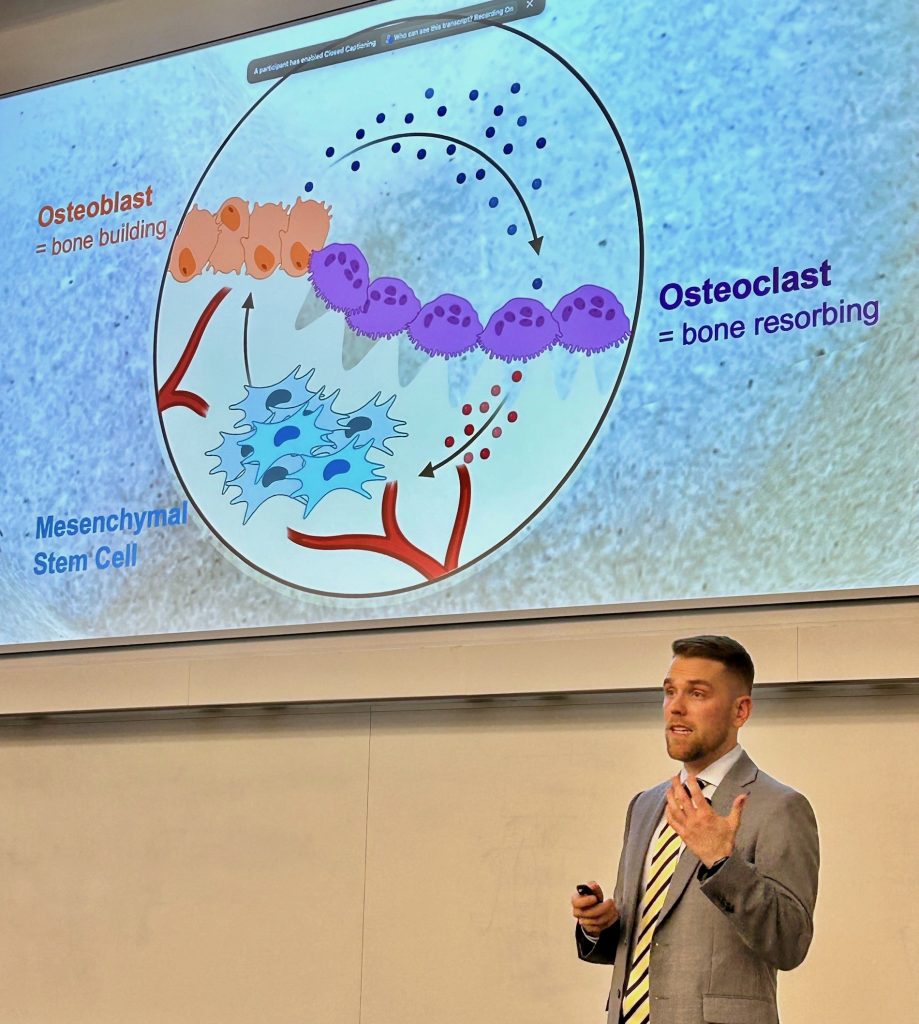

Research into tissue regeneration and biomaterials, which has burgeoned over the last 20 years, appealed to Swanson as he considered what type of research to pursue. In the dentistry arena, research into how to regenerate bone – the body’s predominant hard tissue – is important as it relates to preserving and restoring teeth in the upper and lower jaws.

Swanson initially connected with faculty member Dr. Peter Ma, an expert on biomaterials, tissue engineering and drug delivery, who helped Swanson begin his research journey. In the meantime, faculty member Dr. Yuji Mishina, an expert in skeletal biology, became an integral part of his mentoring team. Among the complex and endless elements of bone regeneration science, Swanson mapped out research on how to encourage cells to replicate in order to rebuild bone to repair bone loss caused by dental disease, trauma or genetic flaws. His research includes the use of stem cells and tiny structures called scaffolds that hold of a collection of cells and can include drugs designed to stimulate cell growth leading to bone growth.

“The body already knows how to grow and repair bone. It’s an exercise in how to tell it to do it at the right time and in the right place and the right shape,” Swanson said. “We need to develop a biomaterial that keeps stem cells happy in a complex microenvironment, to allow them to do their job and respond in a normal way but not all at once. In that way, they can contribute to tissue formation over time. It is sort of a repair kit or growth center built into the bone.”

Over the course of his research, Swanson developed a third mentor, Dr. Colin Greineder, assistant professor of Emergency Medicine and Pharmacology and member of U-M’s Biointerfaces Institute, who furthered Swanson’s understanding of drug delivery.

Over time, Swanson began to publish his research with various faculty members and outside researchers as co-authors. His CV now includes more than 20 high-end scientific publications in various journals, where he uses his formal name, W. Benton Swanson. Here’s a brief selection of the research on his CV, using the scientific vernacular:

• Developed novel methods for encapsulating and releasing extracellular vesicles to treat critical-size tissue defects in vivo. Characterized biologic responses to cell-specific exosomes and attributed function to miRNA.

• Developed a three-dimensional scaffold platform to re-establish a skeletal stem cell niche in vivo in craniosynostosis models. Elucidated molecular mechanisms related to the pathogenesis of craniosynostosis in BMP-overexpressing mouse model. Determined how spherical micropores influence in vitro cell differentiation and in vivo construct phenotype specification attributed to YAP/TAZ regulation.

• Investigated the response of osteoclasts to synthetic nanofibrous biomaterial microenvironments. Determined involvement of osteoclasts in biomaterial scaffolds and contribution to blood vessel maturation in engineered bone tissue.

After those projects and others, the result was his dissertation titled: “Regenerative Engineering in the Bone Microenvironment: Towards Reestablishing Homeostasis and Function Using Implantable Biomaterial Scaffolds.”

Destination in sight

On a Thursday afternoon in mid-January, Swanson stood at the front of a School of Dentistry lecture hall for his dissertation defense. About 75 people, including his parents, were in the audience. Others, including some of his dissertation committee members and mentors, were watching via Zoom from across campus and around the country.

His Dissertation Committee is William Giannobile, a former U-M dental school faculty member who is now Dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine; Evan Keller, a professor of urology and pathology at the U-M Medical School; Yuji Mishina, professor at the School of Dentistry; Lonnie Shea, professor of biomedical engineering, chemical engineering and surgery at U-M; and Megan Weivoda, a former assistant professor at the School of Dentistry who now leads a research program at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Introduced by Dr. Mishina, Swanson opened his presentation by thanking his mentors “who challenged me in ways I didn’t know I could be challenged or needed to be challenged.” He also thanked the 15-plus undergraduate and master’s students who were part of his research projects at the dental school. “I’m incredibly grateful for the environment to work and grow in over the last seven years,” he said. Backed by PowerPoint slides to illustrate his research, he offered an articulate, brisk-paced presentation that included a brief history of tissue generation and the detailed nuances of his latest scientific research into bone scaffolds.

With input from his dissertation committee, the final version of the document has been successfully approved.

On the DDS side, he’s completed nearly all of the clinical care requirements. Most of his clinic work now is finishing treatment plans that were already underway and must be completed before his time with the patients comes to an end because of graduation in May.

After seven years, and thanks to the dual degrees, Swanson’s CV is an impressive list of accomplishments beyond the scientific research publications. He lists numerous presentations around the country and at several international conferences; several funding awards, including a fellowship from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; numerous fellowships, scholarships and travel awards from the Rackham Graduate School, School of Dentistry, and national and international dental research organizations; a range of clinical experience that goes beyond the walls of the dental school to other Michigan communities; teaching experience; and public and academic service activities.

“It’s a long time, seven years,” Swanson says, noting that several people had pointed that out in advance when he was considering this academic path. “A lot of life happens in seven years. A lot changes in seven years. The field certainly changes. Things I couldn’t predict about the training. But I wouldn’t change anything about it.”

What’s next?

This spring, after graduation, Swanson is headed to Harvard University School of Dental Medicine for a three-year residency in periodontics that will allow him to continue his current research path. He will work again under Dr. Will Giannobile, the former U-M dental school faculty member, now dean of the Harvard dental school and a mentor who was one of Swanson’s Dissertation Committee members.

It’s an important connection for Swanson because Giannobile is a leading scientist-clinician in translating research findings into patient care solutions through clinical trials. Swanson says he learned from Giannobile to consider research that is “patient-driven, where there is a true clinical need at the heart of your question.” Moving the scientific findings into health care is a process that often involves companies – or researchers themselves acting as entrepreneurs – in creating products and methods that clinicians can use to treat patients.

Swanson already had an interest in business applications when he began his training at U-M, but working with Giannobile and other mentors prompted him to enroll in the extra courses at the Ross School, as if the DDS and PhD curricula weren’t enough. Taking in night classes and seminars over three years, Swanson and world-class lecturers explored a rich variety of topics, including venture capital, business creation, teams and leadership, billion-dollar “unicorn” start-up companies, and lessons learned from failed biotech companies. Swanson also joined the U-M College of Engineering’s Graduate Certificate in Innovation Entrepreneurship, an add-on for PhD students.

Swanson said Harvard’s location in the Boston area will provide exceptional access to many academic, medical, commercial and investment interests currently working in close proximity in the biotechnology sphere. The area is home to multiple universities, medical centers, private bio-tech firms, venture capitalists and entrepreneurs.

“Business is a vehicle that allows us to get these research discoveries out into the world,” Swanson said. “How university innovation spins out into companies and interfaces with the clinical world – I think that’s just fascinating. That’s really where I want to see myself in my career, at that intersection of getting things out into healthcare practice. I want to be able to point to something and say I had a part in getting this to the clinic and that it has changed the way we treat patients and it is improving outcomes. There were a lot of amazing opportunities here at Michigan to get my feet wet, and Boston will be a great place to continue that.”

A label near the top of Swanson’s CV sounds like a job-search pitch, but it precisely captures where he hopes to head next: “Clinician-engineer passionate about developing new technologies at the intersection of tissue engineering, materials science, and innovative chemistry to unlock the next generation of precision medicine therapies.”

That career goal meshes well with one of the things he learned when he met his first PhD faculty researchers 10 years ago at Canisius – “they were faculty but still students” in their quest to keep making discoveries.

“In dentistry and research, you can always keep learning,” Swanson said. “You are a lifelong student learner. I don’t want to get bored. There were a lot of things I looked at as careers and I thought I might have fun for a year or five years, but not long-term. With this, you wake up every day and ask questions. There is always something more to learn and try.”

###

The University of Michigan School of Dentistry is one of the nation’s leading dental schools engaged in oral healthcare education, research, patient care and community service. General dental care clinics and specialty clinics providing advanced treatment enable the school to offer dental services and programs to patients throughout Michigan. Classroom and clinic instruction prepare future dentists, dental specialists and dental hygienists for practice in private offices, hospitals, academia and public agencies. Research seeks to discover and apply new knowledge that can help patients worldwide. For more information about the School of Dentistry, visit us on the Web at: www.dent.umich.edu. Contact: Lynn Monson, associate director of communications, at [email protected], or (734) 615-1971.