Alumni Profile: Jerome DeSnyder, DDS 1967 – A long, successful career emerged out of a challenging era16 min read

This profile is one in an ongoing series highlighting School of Dentistry alumni, donors and students.

––––––––––––––

When Dr. Jerome “Jake” DeSnyder looks back on the more than 50 years he spent as a dentist, he feels a deep sense of fulfillment. It was a great run, with nearly all of his career logged in Plattsburgh, New York, a scenic city of about 20,000 along the northwest shore of Lake Champlain in northern New York.

The 1967 graduate of the University of Michigan School of Dentistry started his career with three years as a U.S. Army dentist in Okinawa during the Vietnam War. He returned to Michigan to work as an associate at a practice in Saginaw for a year and a half, then moved to Plattsburgh, where he practiced from 1971 until retiring in 2010. He didn’t really retire, though, because for the next eight years he worked two days a week, from May to October, at a clinic for low-income patients in a city 50 miles from his home. In 2018, he finally hung up his handpiece for good, 51 years after he started.

“The satisfaction for me was providing something that I knew was going to improve my patients’ lives day to day,” he said. “But also I got a kick out of dealing with people every day. I loved it. So it was two things – the fun of dealing with the patients and then I’m providing something that’s good for them.”

Beyond treating patients at his practice, DeSnyder had taken his skills throughout the community for decades, treating nursing home patients for nearly 30 years and Head Start children for nearly as long. He had regularly teamed with a local oral surgeon to treat children with special needs. From the start of his career he was active in professional dentistry at the local, state and national level, serving on several ground-breaking committees. He was well-known in the Plattsburgh community for his work with the Rotary service club and as a youth hockey coach.

“So I touched not just the mainstream, but a lot of the community, which I did on purpose because I liked doing it,” he said. “Those things gave me a much broader presence in the community, which I loved. I loved going to the nursing home. I developed a lot of friends there. I always loved dealing with and coaching kids, so the Head Start was fun, too. My practice in general was very rewarding for me. I never thought a lot about it at the time, because you are busy living.”

But then he retired and the community responded in a way that touched him deeply. When he sold his practice for his so-called first retirement, his staff and his wife Lynn insisted there should be a party at his office building. “We sent out notices to all the patients and we had people lined up around …,” he pauses in a moment of emotion. His wife Lynn finishes the description: “People were lined up around the block. Hundreds of people came. It was very much a validation of everything he’s about, which I would say is the model of Rotary: Service above self. He’s lived a life just like that.”

DeSnyder, initially unaware of the size of the crowd, greeted each patient in the reception line with his usual gift of gab. “My office manager came over two or three times and said, ‘Doc, you gotta quit talking so much, they’re lined up around the building.’ After it was over, seeing all those patients made me really appreciate that my career was a two-way thing. It made me realize that what I was feeling as far as satisfaction, my patients did, too.”

Choosing dentistry

Growing up in Fair Haven, Michigan, on Anchor Bay on the north side of Lake St. Clair, DeSnyder spent a lot of time on the water and playing sports. As the first in his family to go to college, he considered choosing a small Michigan college where he could play football. But he credits a guidance counselor at his high school – known as Miss Stewart – with steering him toward bigger things. She gave him a University of Michigan catalog and told him he could find whatever he liked most among the many courses it described. She also told him she could find scholarship money for U-M, which was important for the oldest of four siblings in a blue-collar family.

At U-M, DeSnyder played on his love of math and science to consider a medical career first, but hesitated because he knew doctors who seemed to work seven days a week. He also worried about how he would deal emotionally with the fact that doctors’ patients sometimes die. Influenced by the example and encouragement of his family dentist, who was the father of one of his high school friends, DeSnyder switched his focus to dentistry. He was admitted to the U-M dental school after only three years of undergraduate study.

His four years at the dental school, from 1963-1967, were defined by two historical aspects of the era. As many graduates of 1960s will attest, faculty were extremely demanding in their dealings with students. Then there was the Vietnam War, which affected college life on every corner of the campus. DeSnyder found a way to navigate through both.

“Initially, what struck me when I got into dental school, was that they didn’t treat us real well. I had the impression they were trying to weed us out. Inside my head, I thought: I’m good enough to be here, I don’t need you trying to get rid of me. It was completely different with the med school guys I knew. For them, it was like ‘Ah, the golden boys are here.’ So that was my first impression. I was a kid then and that structure didn’t hit me exactly right. I thought I was a pretty important guy: I can do this, let me loose. They treated you almost as if they were adjunct parents.”

Sometime in his second year, he began to appreciate the structure of the dental school as he noticed the wide range of skill levels among his classmates. The faculty’s job was to raise all of the students to a high level. “After you are here a little while, you figure out that these people – the faculty – are trying to mold someone who is going to be in practice for 40 years. They want you to be sound clinically, with sound judgment. You don’t have to be a genius to figure out you’ve got world-renowned people on this faculty. Bob Moyers in orthodontics. Ralph Sommer in endodontics. Frank Smith in prosthodontics. Sigurd Ramfjord, he was a legend. I began to appreciate that after the first year or so. And I realized: I’m lucky to be here. Let’s dig in here, baby, and let’s learn what we can. I wanted to be one of the good guys.”

Dental school during a war

It is a School of Dentistry scene that is difficult to imagine today – unless you were sitting in one of the seats in the lecture hall that day in 1965.

Second-year dental student Jake DeSnyder attended an all-school assembly with speakers from the U.S. military. A few months earlier, in August 1964, the run-up to the Vietnam War had been ignited by what later became known as the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. An encounter between a U.S. ship and North Vietnamese torpedo boats led Congress to approve the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which in turn led to the use of military force against North Vietnam and the start of the Vietnam War.

DeSnyder remembers the stark message of the military speakers that day. “They told us we were all going to be drafted as soon as we graduated because this Vietnam thing was taking off.” As an alternative, the speakers said, dental students who enlisted while they were in dental school would enter at a higher rank and, thus, higher pay after they graduated and became military dentists. Also, their time in dental school would be counted as part of their six-year commitment, thus reducing how long they would need to be in the military. Another implied benefit, if not explicit promise, was that enlisting would lessen their chances of being sent to Vietnam, which didn’t always prove true as the war expanded.

DeSnyder and several of his classmate friends weighed their options. They were already considering their post-graduation future and how to find a dental practice in order to start their careers. Being drafted would complicate that process. They realized that practicing in the military would be like graduate dental school, with a paycheck, and would likely help jump-start their private careers when they left the military. DeSnyder, his friends and a significant number of their Class of 1967 decided to enlist. DeSnyder joined the U.S. Army. He still has the enlistment document he signed in March 1965.

While today a significant number of dental students become military dentists upon graduation, usually as part of a military scholarship program, in the mid-1960s there was much more of a dark cloud of uncertainty hanging in the air. Dental students knew they might end up in a war zone. DeSnyder was happy to learn even before he graduated that he would be sent to Okinawa, Japan, after a few weeks of Army indoctrination at Fort Sam Houston in Texas.

Okinawa was a major U.S. staging ground for supplying military operations in Vietnam. It had excellent military medical facilities that served dual functions. Doctors and dentists treated military personnel wounded in the war and also provided medical and dental care for the huge contingent of military personnel and their families stationed on the historic island.

Joining DeSnyder were two of his U-M dental school classmates, Al Fears and Vic Ratkus. They were among about 50 dentists – 30 in the Army, a few less in the Air Force and one Navy dentist serving the Marines. As the three Wolverines moved through their dental duties on Okinawa, they discovered that they were among the best-trained dentists. “We talked about it. We came out of dental school in better shape than these other guys. And we realized that maybe we had a little bit of a bad attitude about dental school. That’s when it dawned on me for real: I’m well-prepared and I’ve got to thank Dr. Moyers and some of those other hard guys who were on the faculty.”

In typical Michigan leadership fashion, DeSnyder helped start the Okinawa Tri-Service Dental Society as a sort of continuing education program where the dentists could share and discuss their dental cases. They worked with their well-connected superiors to bring in high-profile speakers from throughout the U.S. military medical and dental leadership to discuss procedures they had completed.

“I saw more dental stuff in three years in the military than I would have seen in practice in 15 or 20 years,” DeSnyder said. “People would come back from Vietnam. We had 30 days to fix them up for their return to Vietnam, or 30 days to stabilize them and send them home to the States. I saw a lot of stuff in the hospital during that period of time that I don’t care to ever see again.”

DeSnyder ended up spending the rest of his entire military commitment on Okinawa. He felt lucky since he knew other dentists who had been stationed stateside in their first year, then sent to Vietnam in their second year. “At some point, I realized that I’m probably going to come out of this alive. I was thankful I wasn’t running around in a tent in the jungle.”

On to a career

DeSnyder returned to Michigan in early 1970 and found a job with a dentist in Saginaw, where he stayed for a year and a half. Remembering how much he was impressed by part of the northeast U.S. during an earlier trip there, DeSnyder returned to explore locations where he might open a dental practice. He traveled with a dental company salesman who was familiar with the parts of New York and Vermont that surround Lake Champlain.

He chose Plattsburgh on the New York side of the lake, impressed by the friendliness of the community, its good educational system and the lack of any protective turf wars among the dentists in the area. He remodeled a house to create an office and opened his practice, perhaps fittingly for a veteran, on Pearl Harbor Day, Dec. 7, 1971. It was not an ominous beginning. If it sometimes takes time for new dentists to draw patients, that wasn’t the case for DeSnyder.

“When I walked into my practice on the first day, I had a full schedule. Four of the local practitioners were saving patients for me. I was busy that first day and I never had a quiet time after that, either.” Those first four dentists, plus others in the area over the years, referred patients with various types of dental needs, including endodontics in the early years when the community lacked an endodontist. The local military air base also supplied a steady stream of patients, as did the network of parents he befriended as a youth hockey coach.

His practice went well over the years. The collegiality in the local dental community was so strong that in 1977 DeSnyder joined with two other general dentists and an orthodontist in a rather unusual collaboration. They designed a new building that they shared. A common waiting area in the middle was surrounded with a different dentist’s office on each of the four corners. He said they took pride in how well they got along in the close quarters over the years.

Beyond the fulfillment he expressed about helping patients, DeSnyder also takes satisfaction for bettering dentistry through his work with various local, state and national professional organizations. He chaired both the New York and American Dental Association’s Council on Dental Practice, which examined all manner of elements affecting dental practices, including a period of time when the profession was dealing with contaminated metal in materials coming from international dental labs. He was the New York representative on a regional study on dental practice wastewater that sought to contain mercury and other contaminants. The initial study, a collaboration of the National Wildlife Federation and the Vermont State Dental Society, later served as a model when the issue expanded to the ADA, where DeSnyder also participated. It led to new regulations for trapping pollutants in the waste stream. He also worked with the New York dental association in its first collaboration and a later update with the American Heart Association for pre-medication guidelines for dentists.

“It was some major stuff that it was fun to be a part of,” he said. “You felt like you were doing something for the profession.”

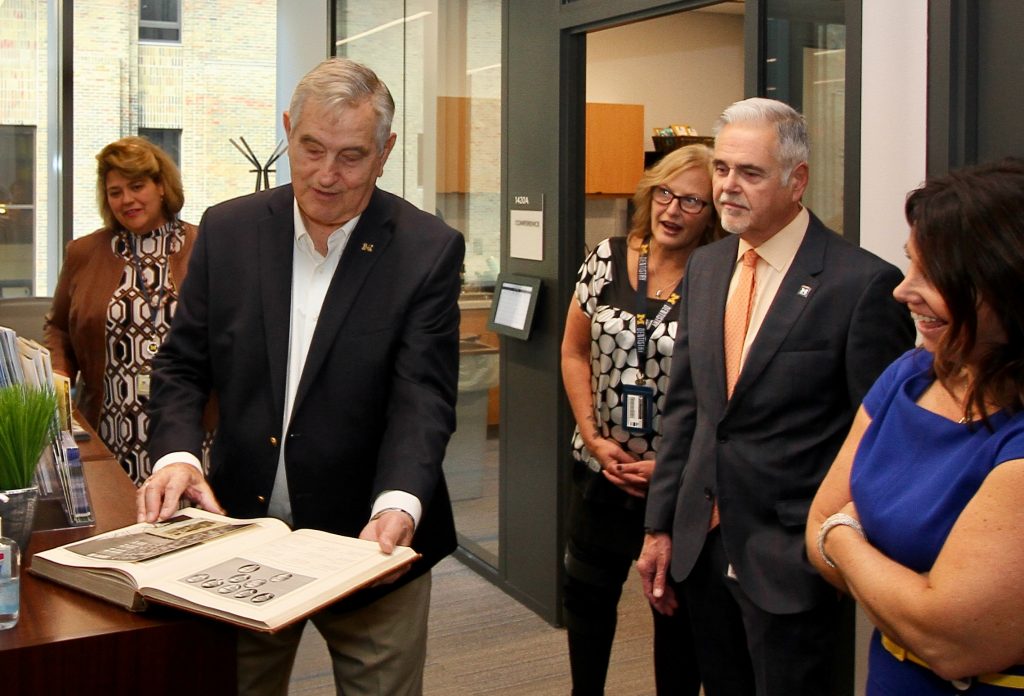

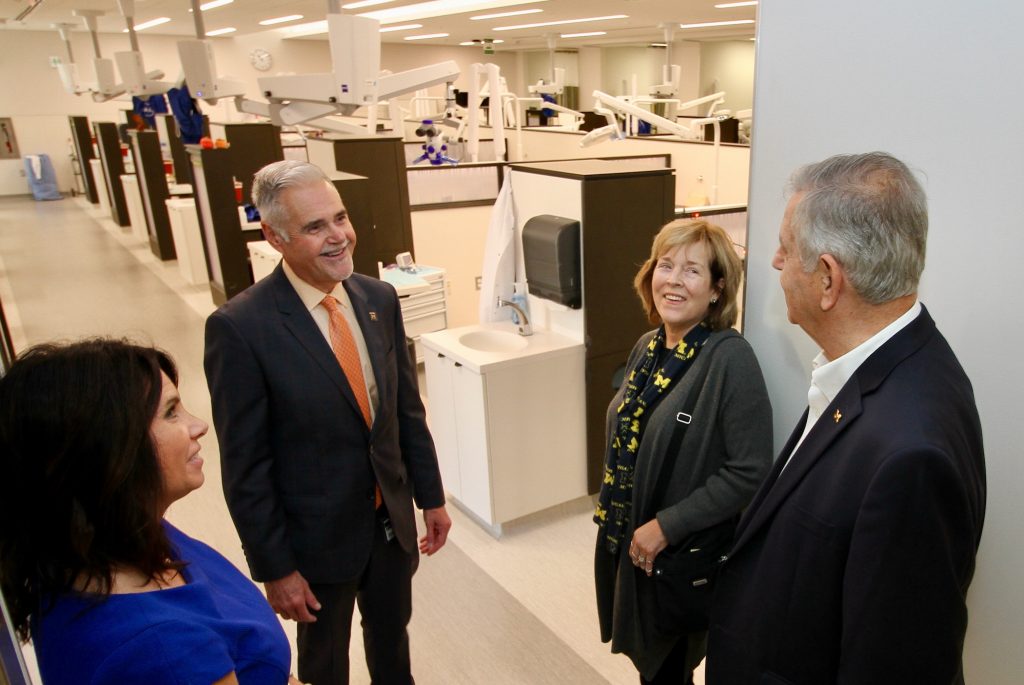

These days, he’s keeping contact with the profession by serving on the School of Dentistry Alumni Board of Governors, which brought him to Ann Arbor recently. He said it was fun to tour the recently renovated school and compare his 1960s experience with how today’s students are educated.

That sort of reflection is at the heart of retirement. A while back, DeSnyder put together some of his history to share with family members. It’s easy to forget some of the chapters and many of the stories unless you make an effort to write it down and document the facts. Like going to Louisiana in 2005 to help residents there clean up after Hurricane Katrina. Or the mission trip he and Lynn took with 13 dentists in 2009 to treat people living in villages in the Andes Mountains of Peru.

In retirement, he continues his love of boating and traveling. He and Lynn spend winters in Florida. They each have two children in their blended family, which provides some of their destinations. In this more relaxed stage of life, as Jake muses in hindsight about his career, he likes how it went and how he learned things at every step of the way, from dental school to the Army to treating patients day after day for so many years.

“It was a good career,” he says. All those hundreds of patients who stood in line that day at his retirement reception would agree.

###

The University of Michigan School of Dentistry is one of the nation’s leading dental schools engaged in oral healthcare education, research, patient care and community service. General dental care clinics and specialty clinics providing advanced treatment enable the school to offer dental services and programs to patients throughout Michigan. Classroom and clinic instruction prepare future dentists, dental specialists and dental hygienists for practice in private offices, hospitals, academia and public agencies. Research seeks to discover and apply new knowledge that can help patients worldwide. For more information about the School of Dentistry, visit us on the Web at: www.dent.umich.edu. Contact: Lynn Monson, associate director of communications, at [email protected], or (734) 615-1971.