Donor Profile: Dr. Reggie VanderVeen (DDS 1976) – a lifelong commitment to advancing dentistry15 min read

This profile is one in an ongoing series highlighting School of Dentistry alumni, donors and students.

Ann Arbor, Mich., Feb. 10, 2021 – It would be difficult to find a resume with more service to the profession of dentistry than the one that Dr. Reggie VanderVeen has lived out over the last 45 years or so.

Reading his resume is no short story. It is a lengthy list of activities for local, state and national dentistry organizations. The dates of his service started early in his 30 years of practicing in the Grand Rapids area and continued after his retirement in 2008, although in the last few years he is finally pulling back a bit.

VanderVeen has been part of so many associations, academies, boards and committees that it seems likely he is an expert on Robert’s Rules of Order – which is confirmed about halfway through his resume where it lists his decade of membership in the American Institute of Parliamentarians.

An abridged list illustrates the breadth of his involvement:

• The Michigan Dental Association – Selected activities from 1976 to present: House of Delegates member and alternate; Legislative Contact Dentist; Annual Session Committee chair; consultant to the Special Committee on Licensure; Committee on Endorsed Investment programs of the MDA Insurance and Financial Group; consultant to the Scientific Program Committee.

• Michigan State Board of Dentistry – 2002-06, appointed by Gov. John Engler.

• The American Dental Association – Selected activities from 1976 to present: consultant site visitor for the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA), 2011-14; member of the Joint Commission on National Dental Examinations, 2011-15, and Vice Chair 2014-15.

• The American Board of Dental Examiners (ADEX) – Board of Directors, 2010-13; Michigan State Board of Dentistry Representative, 2007-10; chair of the Articles of Incorporation and Bylaws Committee, 2005-07.

• Northeast Regional Board of Dental Examiners – Committees he served on or led include Constitution and Bylaws, Public Advocacy, State Action Team Leader, Steering, ad hoc Policies and Procedures and Website Development.

• American Association of Dental Boards – Member 2001-10; Chair of the Constitution and Bylaws Committee, 2004-2008; Chair of the ad hoc Membership and Dues Structure Review Committee, 2010.

• West Michigan District Dental Society – President and numerous other offices; member and chair of several committees, including Hospital-based Dental Residency Program Task Force, Bylaws, Membership, Programs and Arrangements, Editorial Policies, National Children’s Dental Health Month, and Legislation.

• Other dental organizations – American College of Dentists; International College of Dentists; Pierre Fauchard Academy; U-M School of Dentistry Alumni Society Board of Governors, chair 2013-14; and the dental school’s Campaign for Michigan and Victors for Michigan fundraising campaign committees.

• Other community service – Children’s worship leader, marriage seminars facilitator and mission society participant for his church; Cub Scout leader; Kent County Community AIDS Council; Kent County Oral Health Coalition; founding member of Clinica Santa Maria, a Hispanic population dental clinic; and board of directors for the Black Forest Property Owners Association.

These days VanderVeen laughs at the thought of being involved in so many positions of authority in dentistry and community organizations after what he calls his “radical” student years as an undergraduate at the University of Detroit Mercy and then at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Growing up in a working-class family in Grand Rapids, VanderVeen admits he had a bit of a chip on his shoulder when it came to dealing with the people who made the rules. And maybe the fact that dentistry skills came easy to the kid with the great hands added to the problem. Those were also the days of the Vietnam War – the late 1960s and early ‘70s – with the possibility of being drafted, war protests and national politics hanging over the students’ daily lives. Dental school was much tougher than undergrad had been, in part because many of the faculty were military veterans who had served in World War II and the Korean War. They weren’t accustomed to having the chain of command and their authority questioned.

VanderVeen’s days of pushing a bit too hard against faculty and school rules came to an abrupt end when he was called to the Dean’s Office during his junior year. A group of faculty made clear it was going to be their way or the highway for this third-year student. He might have to forfeit his third year and all the tuition money he had spent, or add a year or get kicked out entirely, unless he agreed to an attitude adjustment. He did, and he says he was a model student the rest of his junior year and senior year before graduating in 1976.

VanderVeen says he was a student who needed a lesson in discipline. “I think that was the most important turning point for me – to understand that I’m responsible for making me the person who deserves to be licensed to practice dentistry. Later throughout my career, I became this authoritarian guy for my profession and it made sense to me, but I didn’t know it when I was a junior in dental school.”

With benefit of hindsight and the wisdom that comes from three decades of practicing dentistry, VanderVeen understands now that the dental school and its faculty were molding students in the time-tested ways that had proven to turn out practitioners of the highest level. He has lots of positive memories as well. He remembers professors Don and Ron Heys for their clinical expertise and positive manner, along with Walter Kovaleski, who lectured on the occlusal adjustments needed to establish a stable bite. The lasting lesson in Oral Diagnosis with Professor Dean Millard was that listening to the patient is imperative; don’t get so lost in diagnosing and writing a treatment plan that you miss what the patient is telling you.

“One of the important things that I learned from the faculty was equal treatment. They really did instill that you have to be ethically based and soundly educated. They also made you understand how to self-assess. You had to be the ultimate critic of your work product. They gave you the confidence necessary to be open and honest with your abilities when you were going to get out and be licensed to practice dentistry. I think they did a wonderful job of making certain that they were going to put their DDS on someone who could carry through for a career in dentistry.”

There is no regret or bitterness today when VanderVeen talks about his dental school days. He is an unabashed supporter of the school and what it gave him, his classmates and generations of dentists. It’s far more than merely clinical skills. There’s also critical thinking, attention to detail, scientific foundations, high standards, and the quest for continual, lifelong learning. “The University of Michigan forced you to develop the proper habits to become a successful practitioner. Dental school didn’t squeeze out all of the radical, anti-authoritarianism bones in my body, but they were squeezed properly to the point where I got through.”

In 1976, VanderVeen took his newly minted DDS degree to Saginaw, Mich., where he joined another U-M alumnus, Dr. Reid Calcott (DDS 1968). It was a successful first year and VanderVeen loved treating the many blue-collar auto workers on the practice’s patient list. He could relate to them because he had worked at an auto plant in his hometown of Grand Rapids when he was in college.

Perhaps over-confident because the first year out of dental school had gone so well, he decided to return to his hometown and start his own practice from scratch. He packed up his few possessions in his new Cadillac Eldorado and headed back home to his new office in Wyoming, on the south side of Grand Rapids. It was a decision that would create a “starving dentist” story that the gregarious VanderVeen has shared countless times since.

The only patient he had in his first two weeks was an elderly women who needed her partial denture adjusted. It was such a simple fix that VanderVeen didn’t charge her. “I didn’t make a dime the first two weeks of my practice,” he says. “I’ve got all this equipment – an operatory, another chair, all this stuff. I’m thinking I’m going to starve to death. I’m driving around in a 1977 Eldorado and I don’t have any money coming in. I’m the most broke dentist driving a Cadillac. Starting the practice was the biggest chance I ever took in my life, but it was the smartest chance I ever took.”

It was also smart to not charge that first patient for her denture adjustment. She was so impressed that she apparently told everyone she knew about the nice new dentist in town. “She ended up sending me at least 200, maybe 300 patients – relatives, friends and everyone else,” VanderVeen said. His practice grew steadily and within a few years it was everything he had hoped for. Just as in his first year at Saginaw, a significant number of his patients were auto workers from the plant where he had worked in college, less than a mile from his office.

Nine years into his practice, one of VanderVeen’s early mentors, Dr. Donald Goris (U-M DDS 1946), decided to retire. He declared that he was going to sell his Grand Rapids practice to VanderVeen, who at first declined. But Goris was insistent and VanderVeen eventually saw the advantages of expanding his patient base. For 13 years, from 1986-99, VanderVeen operated both the Grand Rapids and Wyoming general dentistry practices, adding associates as needed at the Wyoming location. In 1999, after deciding two locations were one too many, VanderVeen sold the former Goris practice and returned to practicing solo only at the Wyoming practice, which he maintained until 2006.

His early retirement in 2006, at age 56, was the result of a common dentist malady – neck problems. Two surgeries didn’t fully correct the problem and left VanderVeen frustrated because, he jokes, he could no longer operate at his usual “breakneck speed” of moving through his daily schedule of patients. At the advice of his surgeon, VanderVeen chose medical disability rather than risk further deterioration of his neck condition by continuing to practice.

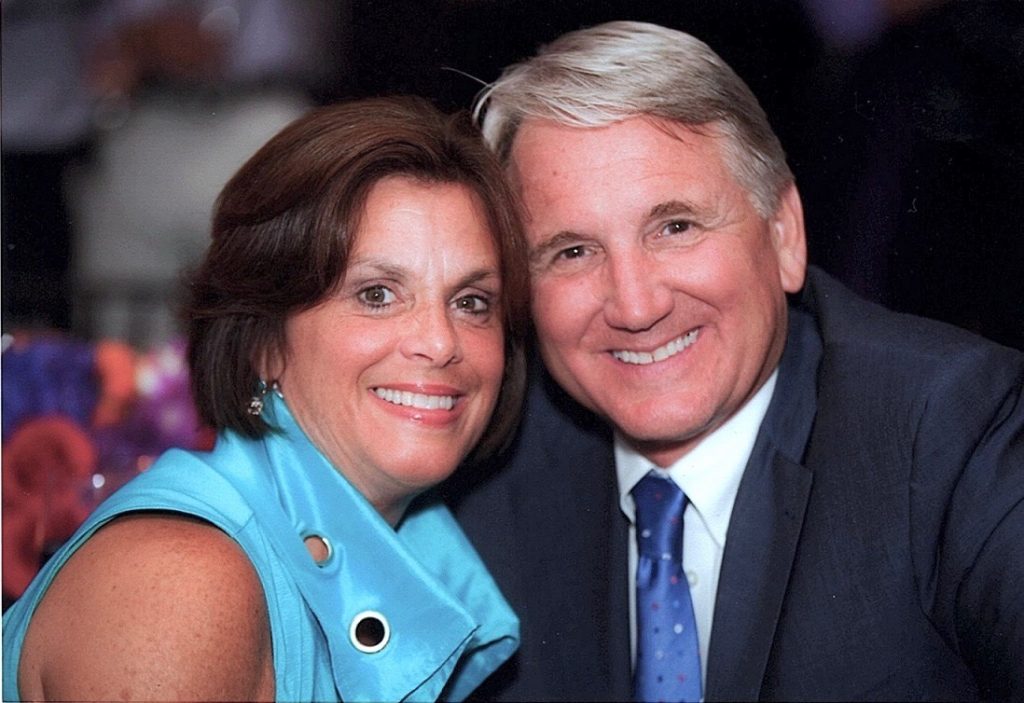

Early retirement took some adjustment, for both VanderVeen and his wife, Gayle, who was the business manager of his practice (after working as his dental assistant briefly in the early years of his practice.) Golf is great but not a year-round option in Michigan, and wintering in Florida away from longtime friends loses its allure after a while. After about three years, Gayle told Reggie he needed to find a new job. Not long after, a friend alerted him to an opportunity with a dental consulting business. In 2010, he joined Henry Schein Professional Practice Transitions, working mostly in Michigan to assist dentists as they bought practices or retired from practicing.

Thirty years of practice experience and a retirement, particularly an early retirement, provided a lot of good touchstones for VanderVeen to cite for the wide variety of dentists he met over the seven-plus years he consulted. His first question for dentists considering retirement: Are you ready, not financially, but emotionally? Often the dentist’s spouse was a better judge of that.

To reach an even broader audience, he created several presentations that were either posted as videos on the Internet or delivered at conferences, including: “How to Purchase a Dental Practice,” “Tips for Successful Associateships” and “Job Search Skills – What Works, What Doesn’t, What to Know.”

Now that he’s approaching the third year of being officially retired, VanderVeen looks back on a successful career and life that he couldn’t have imagined when, as an eighth-grader, he decided he wanted to be a dentist. He says he decided on dentistry for perhaps the wrong reasons. The family of a neighborhood dentist had a nice lifestyle and the dentist worked regular hours. The dentist’s family was quite different from VanderVeen’s working class family, which revolved around his father’s 60-hour work weeks as a salesman. “I thought dentistry looked like a pretty darn good profession,” he said.

All these years later, he has confirmed that assessment, but not only because it provided a good living. The relationships he formed with his thousands of patients, his ability to restore and maintain their oral health, and his commitment to serve the profession of dentistry have enriched his life in countless ways. Others have noticed his tireless commitment to dentistry and his western Michigan community. He’s received several awards from dental organizations and his community, including the prestigious Silent Bell Distinguished Service Award from the West Michigan District Dental Society in 2008.

His second retirement affords him the opportunity to relax more with family – the VanderVeens’ son Nick is a lawyer in Grand Rapids and their daughter Gina works in public health in Denver, Colo. He’s also committed to supporting Gayle in her work with the Mary Free Bed Guild, the entity that supports the Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital in Grand Rapids. There’s still plenty of time to hang out with his golfing buddies and dentist friends, regaling them with the thousand or so stories he keeps handy in his memory bank.

VanderVeen has returned to the School of Dentistry regularly during his career, serving on and chairing its Alumni Board of Governors; serving on the dental school committees for the last two major fundraising campaigns by the university; and making significant financial gifts to the school. He says his continued ties to the school are an acknowledgment that it contributed not only to his success, but to the success of the profession.

In his many trips around the country for his dental examiner duties and more informal personal tours, VanderVeen has visited about 25 of the 78 dental schools in the U.S. and Canada. He has always come away with the sense that the U-M dental school is indeed a leader in dental education. “Given all that I’ve seen out there with my experience – I’ve visited a lot of dental schools, I’ve seen a lot of problems, I’ve seen a lot of bad actors. But the good actors and the excellence that’s out there don’t have enough light shined on them.”

Staying in touch with the school and contributing to it, financially and otherwise, is “the common sense thing to do, it’s the right thing to do,” VanderVeen said. “It’s different than when we went there, but I know what it takes to create good men and women to practice our profession and the University of Michigan School of Dentistry does it.”

VanderVeen recently committed to a financial gift that includes a naming opportunity for a dental cubicle as part of the Blue Renew renovation project underway at the school. “The University of Michigan School of Dentistry is worth supporting,” he said. “And fortunately, Gayle supports that, too, because we owe an awful lot about where we are right now to what I went through at dental school before she even met me. I felt kind of funny putting my name on a cubicle, but there’s a story there, behind that name Reggie VanderVeen.”

###

The University of Michigan School of Dentistry is one of the nation’s leading dental schools engaged in oral health care education, research, patient care and community service. General dental care clinics and specialty clinics providing advanced treatment enable the school to offer dental services and programs to patients throughout Michigan. Classroom and clinic instruction prepare future dentists, dental specialists and dental hygienists for practice in private offices, hospitals, academia and public agencies. Research seeks to discover and apply new knowledge that can help patients worldwide. For more information about the School of Dentistry, visit us on the Web at: www.dent.umich.edu. Contact: Lynn Monson, associate director of communications, at [email protected], or (734) 615-1971.