Donor Profile: Dr. Steve Dater of Rockford, Mich.13 min read

Service to dentistry, community, country and more

This profile is one in a series highlighting School of Dentistry alumni, donors and students.

Ann Arbor, Mich., Nov. 27, 2018 — Dr. Steve Dater spent the first 25 years of his professional life representing dentistry in many ways, from the local level in west Michigan where he practices to the Michigan Dental Association and the American Dental Association.

Starting a couple of years after he graduated from the University of Michigan School of Dentistry in 1988, his resume documents the many committee assignments and other roles leading up to and after his term as MDA president in 2007-08. At the national level, he lobbied Members of Congress in Washington on dental issues for the ADA’s Council on Governmental Affairs, one of several ADA commitments. He traveled to Ukraine three times on personal mission trips to provide dental care for orphaned children. He served two years on the Professional Advisory Group for Delta Dental of Michigan, and earlier in his career was an instructor and advisor for his local community college dental program. He is currently chair of the Alumni Society Board of Governors for the U-M dental school.

All the while, he has continued his general dentistry practice in Rockford, 15 miles north of Grand Rapids, while raising three children with his wife, Mary. Add in service club and church work, Meals on Wheels and coaching his kids in hockey, baseball and basketball, and you get the idea — Dater is a very engaged leader in his community and profession.

Steve Dater and daughter Stephanie pose with a patient in Ukraine where the dental team used portable dental units and fold-down lawn chairs as dental chairs. In the background is the local clinic coordinator.

Steve, Stephanie and friends at a site in Ukraine.

Steve with two of his young patients in Ukraine.

Three sisters wore what Steve called “their Sunday best” dresses when they came for their dental appointment.

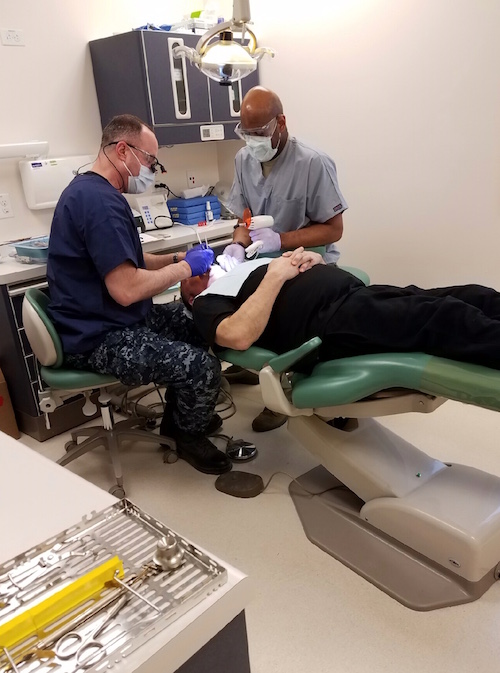

Steve (left) and an Air Force colleague treat a native Alaskan patient at the clinic in Old Harbor, Alaska. The Navy Reserve often coordinates with members of the other military services during outreach clinics.

Steve got a panoramic view of Old Harbor, Alaska, when he and other military personnel climbed a bluff to straighten a letter in a large sign spelling the town’s name, similar to the famous sign overlooking Hollywood, Calif.

And then, five years ago, when most mid-career professionals might think of slowing down a bit, Dater added yet another significant professional — and patriotic — commitment to his life. He joined the U.S. Navy Reserve to share his dentistry skills with members of the military and the outreach missions they perform. His decision came after his daughter, Stephanie, considered joining the Navy to help pay for her dental education at the University of Detroit Mercy dental school. Although she didn’t take that route, she mentioned to the recruiters that her dad, a dentist, had always been interested in military service, so the recruiters turned their attention to Steve. He was 49 at the time, which is eight years past the standard age cut-off for new recruits, but the recruiter wanted Dater’s dental skills enough to offer an age waiver — if Dater could pass the recruit fitness exam. With the help of a trainer and his wife, who is a runner, Dater improved his strength and endurance enough to pass the exam.

Why add such a significant commitment to an already busy life? “It’s something I always wanted to do, I always wanted to give back,” Dater said. “My dad was a Marine. I have a nephew in the Air Force, another in the Army and one in the Navy. I always wanted to serve, but I was always busy with organized dentistry, from 1990 to 2013. If I could look back, I would probably have done the military early in my career and been retired from there by now.”

True to his leadership track record in civilian dentistry, this year Dater was promoted to the rank of Commander to go along with his duties as Officer in Charge of an Expeditionary Medical Facility that sets up dental clinics in various locations around the country. His leadership positions mean he does more than the Reservist’s standard one weekend a month at the Battle Creek Reserve Center and two weeks a year at military bases around the country. Even if it is just answering an email or two, most days he does something related to his Reserve duties. During his two-week commitments, he has treated recruits at the Marine Corps Recruiting Depot in San Diego, Calif., and has provided dental care to Marines at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. His furthest post was in 2017 when he spent two weeks treating native Alaskans at Old Harbor on Kodiak Island. The grateful patients brought Alaskan king crab and salmon as gifts and they hosted a pot-luck dinner for Dater’s military dental team.

That sort of enthusiastic gratitude from underserved patients was also on display during Dater’s three trips to Ukraine, in 2011, 2012 and 2013. In a country that is a mix of modern cities and people using horse-drawn carts in the countryside, Dater and his dental team set up shop in churches, a mayor’s office, community centers or whatever building was available at summer camps for orphans. Their stays lasted 8-10 days. Using fold-down lawn chairs as dental chairs, Dater treated about 30 patients a day. Most were children, but Dater said adults also wanted to take advantage of the American dentists because Ukrainian dentists rarely use anesthetics. He said the hearty thanks and hugs he received from a mayor and border guard supervisor, after he provided them with relatively painless extractions, were examples of the differing healthcare expectations between residents of the U.S. and those in less-developed countries. “People being that thankful, you don’t get that here,” he said.

The Ukraine trips were initiated by Dater’s daughter Stephanie, who wanted to organize a summer mission trip before starting dental school. She found a church-affiliated organization in Virginia called Ukraine Children’s Project, which needed dentists to treat orphaned children. The country was a fitting choice because all of Mary Dater’s grandparents were Ukraine natives. Stephanie served as Steve’s dental assistant the first two years, but was unable to go the third year because of her dental school requirements. “It was a great opportunity for her to make sure she wanted to do this stuff, to see what it’s like to give back,” Steve said. “I think it instilled in her the feeling that you need to use your dentistry skills to help others, you are not just in it to make a living.”

Another very important development in Ukraine was that Stephanie met Cole Waggener, who was there on the same mission project with his father, Rick, a dentist from Florida. Stephanie and Cole kept in touch when they returned to the U.S. and developed a Michigan-to-Florida long-distance relationship that eventually resulted in Cole moving to Michigan. They were married after she finished dental school in 2016, then Cole finished his DDS degree at U-M in 2018. The two now practice in Florida, Cole with his father and Stephanie in a different clinic.

None of the Daters and Waggeners were able to return to the Ukraine after 2013 for various reasons, including a more unstable political climate after Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014. Dental equipment that Steve Dater and other U.S. dentists had purchased and sent to the mission remains there. Dater hopes it is being put to good use for the orphans. “The real sad part is that after three years, we got the mission process down pat,” Dater said. “The kids knew us and they were waiting for us. And now I’m sure they feel abandoned. Like, ‘What happened to the dentists?’”

Dater continues with his busy practice in Rockford, where he does general dentistry, mostly restorative. He likes crown and bridge work and making a patient’s smile better. He doesn’t mind endodontics, i.e. root canals, but his least favorite procedures are the extractions he sometimes must do.

That Dater would have become a versatile dentist who loves his work could not have been predicted when he first started college at U-M as a history major with a couple of science courses and a work-study job in a lab in the chemistry department. One of his favorite stories about being a dentist is how much he hated going to the dentist as a child, all the way up until he became a dentist. As a sophomore at U-M, he wasn’t sure where he was headed until the day he reluctantly followed a friend, Dennis Hartlieb (DDS 1988), to Dental Career Day at the dental school. He was impressed with the presentation and decided to join Hartlieb in trying for admission to the dental school after their third year of undergrad. They both got in.

It was an amazing development for someone who spent a lot of unhappy times at his family dentist. “I hated the dentist,” he laughs at the memory. “I did not have a dentist role model growing up. My dentist was scary to me. I always had cavities. It was my least favorite place to go.” He says one of his jobs as a teenager was in a restaurant where he sipped Coca-Cola during his shifts. The long-term result: he’s had 11 crowns and seven root canals. “I was a bad teenager, what can I say? … I’m a poster child for ‘Don’t do that.’” In the end, however, Dater believes the experience has made him a better dentist. “I think I’m very empathetic. I don’t get upset when people say, ‘Oh, I hate being here.’ I don’t take it personally because I don’t like being on that side of the chair, either.” When patients need a break during treatment, no problem. “When you know what they are going through, I think it makes you a better clinician and an operator,” he said. “For dentists who have never had work done, they don’t sometimes understand that side of the chair.”

Another facet of his dental career that has changed more recently is his appreciation for the School of Dentistry. Dater’s straight-shooting personality led to a fair number of what he calls “run-ins” with faculty and a few failing grades along the way. He prefers to remember several faculty members who were great mentors — Bill Knight, Bill Gregory, Joe Kolling, Don and Ron Heys and Mark Fitzgerald, some of whom are still his friends today. But by the time he left dental school and headed to his first practice in Grand Rapids, then to Rockford a few months later, he thought he would have little future contact with the school. Today, he’s finishing out his second term as chair of the Alumni Society Board of Governors and has made consistent financial gifts to the school, the most recent being $25,000 to name a DDS operatory for the major renovation now underway at the school.

“I think what changed my view was the education I got and the ability to earn a living. That’s something I’m thankful about — hey, U-M let me in,” Dater says with a laugh. “No. 2, working with Jed Jacobson when he was director of admissions, I would go around with him to talk to students about dentistry and he would talk about the school. I saw his commitment to the school. Then when I was on the Board of Governors and meeting people like adjunct faculty member Joe Kolling. When you see what they are willing to do for the school, I think all that makes you think that you should give back, because without the school I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing.”

What he’s doing -– and has done -– has led to numerous awards from his peers in dentistry. Last year, the MDA presented him with its Emmett C. Bolden Dentist Citizen of the Year award. And in early December, the West Michigan District Dental Society will present Dater with its annual Silent Bell Award, describing him as “a role model for service.”

He plans to stay with the Navy Reserve as long as it will have him. He knows the military commitment, plus his dental practice and service to dentistry organizations, will, as it always has, leave him little free time. “I just feel like you should give back,” he says. “We’re blessed to do what we do. I get a little mad because I hear people say, ‘I can’t volunteer because I’m too busy.’ If you can’t make time to give back to your community, or whatever you want to give back to, I think you are missing the boat. I know my wife at times would love it if I didn’t do as much, but she’s very supportive. When I was doing a lot for MDA and ADA, she would come along, and she volunteers for other things, too. It’s just part of our make-up.”

These days, they are adjusting to being empty-nesters. Their son Scott has been in Europe working on an advanced degree in urban planning and plans to return there to finish his studies. Their youngest son, Sam, is a manager at a Michigan grocery store. Daughter Stephanie and her husband, Cole, recently expanded the family by one when the Dater’s first grandchild, Anya, was born. All of that — the family, the practice, dentistry organizations, community service, the Navy Reserve — is a full and rewarding life for Dater. Told that he could cut out half of his service and still be ahead of most people, he admits he sometimes thinks about it. “Someday, I would just like to have a weekend with nothing to do,” he says.